1. LEARNING

1.1. Definition of learning

Typing as a search term on Google "learning" you get the beauty of 2,960,000 different pages. This reflects the great interest that the issue of learning arouses in our similar ones. Human history has always been accompanied by definitions of learning that go hand in hand with cultural and sociological periods. As far as we are concerned, we consider learning as the process of acquiring knowledge, a skill or a particular ability through study, experience or teaching. We therefore place ourselves on the side of those who consider learning as an "experience-dependent" process, since modern neuropsychological theories have shown that experiences significantly influence the neuronal connections of the individual, thus modifying his/her cerebral structures.

If we take into account the strictly psychological point of view, we can state that learning is an adaptive function of a subject's behavior, resulting from an experience, so learning is an active process of acquiring stable behaviors according to the adaptation functions. Learning is adapting.

These two aspects, the importance of experience and adaptation, immediately lead us to reflect on the fact that learning is essentially always linked to change. We all know that even the normal process of maturation of the individual is a change, what distinguishes learning from maturation are the influencing stimuli that are internal in maturation, in learning they are external. So if, in a species-specific optics, the maturation would tend to homogenize the individuals of the same species, learning is in essence a process of diversification among individuals.

With regard to these considerations, it must be borne in mind that changes in short-term behavioral potential, such as fatigue, do not constitute "learning" and vice versa some long-term changes do not depend on learning but on maturation.

Which external stimuli influence learning more?

To answer, we hold as a reference point a Murgio survey that reports the following results:

"Learning in humans is about 83% through sight, only 10% from hearing, the rest from the other senses [..] a recipient recalls on average 10% of what he reads , 20% of what you hear, 30% of what you see and 50% of what you see and hear at the same time. "

(Matthew P. Murgio, Communication graphics, 1969)

When is it, in our development, that you begin to learn? We could say "from the beginning" because the baby learns unconsciously to use his body and language. Learning becomes intentional from the moment they are available:

- greater capacity for storing information

- memory strategies developed

- metacognition, ability to reflect on one's way of thinking

1.2 Reference theories for learning

The main learning theories are based on the three paradigms that have always been contested: behaviorism, cognitivism and constructivism. We try to give a brief overview to compare the common aspects and the differentiating factors, convinced that none of the three can be completely rejected.

1.2.1 Behaviorism

The first behaviourist approach of learning study was the so-called associative learning by temporal contingency (or responding conditioning, or otherwise called classical conditioning) by Ivan Pavlov. This approach studies the learning process through stimulus-response association, and represents its simplest form. Pavlov studied the responding conditioning by observing in the laboratory a salivation reaction of a dog, not only in front of the food, but also in consequence of the sound of the bell that introduced the food. The central element of this model is the association of a conditioned stimulus (by its nature neutral and not relevant, such as the sound of a bell) to a reflex response (salivation for food, called unconditional response, since it is innate, and should not be learned). Food, on the other hand, represents the unconditioned stimulus, since it is the element that causes the spontaneous natural response (stimulus), not learned (unconditioned). If this association occurs in a short period of time, this leads to a conditioned response (salivation) also in front of the conditioned stimulus (bell) and not only to the unconditioned stimulus (food).

Through these studies, Pavlov outlined a learning curve (strength of the vertical axis conditioning by number of unconditioned conditional stimulus-stimulus associations in horizontal axis) from the typical profile, within which before learning increases rapidly after exposure to few associations, then it stabilizes itself, while the successive associations influence less and less. The feature that distinguishes these studies from the memory processes identified by Ebbinghaus is the fact that Pavlov applies his learning responsive to sensory and non-verbal data.

Through the stimulus-response association, it is possible to construct long conditioning chains, for example a conditioned stimulus associated to a conditioned stimulus, associated to a conditioned stimulus, and so on, until it reaches the terminal part of the chain, always represented by an unconditional stimulus.

1.2.2 Skinner's programmed instruction

Operational conditioning works on the principle of instrumental learning. A living being learns that his actions have certain consequences. The hungry pigeon learns to press a lever to feed the food when a certain symbol appears. The reward in the form of a grain of food only corroborates this behavior. The principle of instrumental learning is also subject to the programmed instruction, because (thanks to the instruction) the desired learning behavior is strengthened. In the 1960s, thanks to the advent and evolution of the computer, Skinner's theory was applied to the study programs that were widely used in the USA up to the end of the 1970s.

This conditioning is said to be operating because it is based on operations related to the voluntary muscles. In this case, in fact, learning does not happen at the level of reflexes as in the responding conditioning, but in more complex motor operations.

A particular learning technique, called modeling (in English shaping) has been developed starting from the active conditioning of Skinner. This technique, widely tested on human learning, is useful for gradually modifying a behavior. The first time is rewarded (through a positive reinforcement) a behavior that gradually approaches the one you want to develop (even if only approximate), the second only the executions that progress in a more correct situation, the third one only reward the performances even more correct, and so on. It is important, in order to develop effective shaping, that reinforcements are continuous. Intermittent reinforcements are also possible, but they are more useful for reappearing behaviors that have already been learned. In any case it is fundamental that the same behavior is always rewarded.

The studies on the model of operating conditioning, have, in a nutshell, led to postulate a series of conditions that make learning more effective:

- Learning is faster if the reinforcement immediately follows motor performance

- Interval reinforcement builds less fast learning, but tends to be more stable over time

- The positive reinforcement, at the same time, is more valid and active than the negative reinforcement

- The strength of conditioning is greater if you alternate training sessions with other activities

- Incoherent reinforcements of similar behaviors between them are the starting point for states of learned impotence and neurosis

It is true, however, that, after the time when the stimulus does not correspond to a reinforcement, the learning acquired by the animal disappears. This is because continuity, repetitiveness and exercise are needed in learning.

Drill and practice programs

These are systems that exploit the interactive possibilities offered by technology for the development and routinization of technical specifications related to a certain disciplinary field (for example, the technique concerning the use of reflective verbs in Italian). In general, these systems are developed for training purposes that propose a series of homogeneous exercises, which, very often, to encourage motivation, are inserted in contexts of a ludic type (especially those intended for low school levels). More specifically, these drill and practice systems offer drums of exercises whose solution requires knowing how to use a technical specification. While new teaching contents are introduced with the programmed education model, the so-called "drill and practice" programs are aimed at exercising the concepts acquired. Today the "drill and practice" elements are included, for example, in language study programs. An example: words on the screen are displayed in a vocabulary exercise. The exercise consists in recognizing any spelling errors. The wrong words must be deleted quickly by clicking with the mouse. In this way points against time are added. The degree of difficulty and time can be adjusted to individual skills.

1.2.3 Cognitivism

The cognitivist approach distances itself from the models of behavioral associations by shifting the focus from the concept of association to that of representation, as partly anticipated by Tolman with the concept of cognitive maps.

The main innovation of cognitivism is that of exalting the active role of the subject in the elaboration of the surrounding reality, giving greater importance to the internal processes of elaboration and representation.

The classical theories (pre-cognitivism) of learning are interpreted in an alternative perspective (Rescorla, 1988) in which the concept of "expectation" has a central role. The mind would then formulate in continuous hypothesis about the occurrence of certain events on the basis of previous knowledge and seeking confirmation of them in the interaction with the environment.

It is also worth noting that with the emergence of cognitivism the study of learning undergoes a radical transformation with respect to the previous tradition. If in the behaviorist perspective learning is studied through manifest behavior and treated as a "unitary" phenomenon, in the new cognitive perspective a fragmentation of the scope of investigation is observed and learning is redefined in relation to the different cognitive components involved. In particular, there is a strong association between the study of learning and that of memory, because, in order to learn, it is first of all necessary to know how to code, store, integrate and remember information. In this context, the concept of a schema, understood as a knowledge structure that guides the processing process and is in turn updated on the basis of new incoming information, in a constructive and dynamic process becomes particularly important.

The way in which the knowledge already possessed by a person (schemes, concepts, theories, etc.) influences the acquisition of new knowledge is called "top-down" (vice versa), the way in which instead it is the perceived reality that activates cognitive processes of learning or revision of previous schemes is defined as "bottom-up" (from bottom to top).

Countless additional learning specifications that involve other cognitive processes and skills emerge in cognitivism.

Learning to read, for example, involves the integration of linguistic, mnestic and perceptual abilities; knowing how to drive a car means having good abilities of visuo-motor integration, and attentive abilities; learning in the school environment requires both specific skills, such as calculation and reading, and general skills, such as applying strategies, making inferences and implementing abstraction processes.

On the one hand there is therefore a wide development of specific learning models, on the other hand general models of functioning of the mind are defined, which have strong implications for learning even if they are not specific models or theories of learning.

Another aspect that should be remembered is that the first approach to the study of learning in the cognitive field, which had as its object the study of human information processing (paradigm of Human Information Processing), was strongly influenced by the mind-computer metaphor. This led to the development of learning models between the '70s and' 80s, articulated in a series of rigid steps (production rules), with hierarchical structures similar to those of a program that can be implemented in a computer. J.R. Anderson (1983, 1995) for example on the basis of a model of this type (Adaptive Control of Thought, ACT) has developed computer programs for teaching, in which the student is invited to follow certain procedures to learn and the computer, which has in memory the same rules, provides suggestions or corrects the subject whenever he makes a mistake.

An important turning point in the study of learning and cognitive processes more generally is the introduction of the modular theory of J.A.Fodor (1983, 2001).

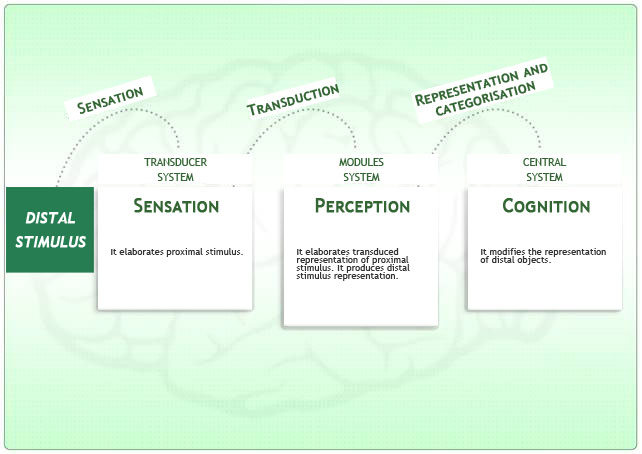

We will not delve into this theoretical hypothesis that is very complex, but it is important to recall the importance for the explanation of the functioning of the mind, of the basic distinction proposed by Fodor, between specific abilities, defined as "modular", and general skills related to the processes of superior thought. Sensory systems by sending the distal stimulus by detecting the environment. The stimuli are elaborated at a first level and are described as innate, highly specialized and efficient, inflexible but very fast in the processing of information and "informationally encapsulated" (they do not have access to the contents and information coming from other modules). A central processor is also postulated, slower in processing but more flexible, which receives data from the modules and has the function of integrating and interpreting specific information.

More recently, the modular model has given rise to criticism and revisions, partly from Fodor himself (2001), partly from the development of alternative models. Karmiloff-Smith (1992) proposes the model of Representational Ridescription which deviates from classical modular theory in that it maintains that there is no central system proper but rather a process called Representational Redescription, which evolves and changes over time with the development. The author claims that the modular processing systems are not innate but are modified and "modularized" with development. Mike Anderson (1992), in the model of Minimum Cognitive Architecture, introduces the most flexible concept of "specific processors" (for example, for the understanding of space) that maintain the functional specificity of the modules, but are not completely isolated from the cognitive functioning general. The horizontal faculties, responsible for the integration of information deriving from specific processors, would instead be determined by a Basic Processing Process (BPM) which is expressed primarily in terms of processing speed and may vary from individual to individual giving rise to differences individual in terms of intellectual abilities. A slow functioning of the BMP could therefore, in some cases, hinder the development of specific processes, which in part depend on it.

In summary we can conclude that the cognitivist approach has completely changed the method of study in the field of learning psychology. Moreover, the theoretical formulations developed in relation to the different learning subsystems have allowed to identify the various cognitive deficient components in the different profiles of learning disorders, thus providing an important contribution also to the clinical field.

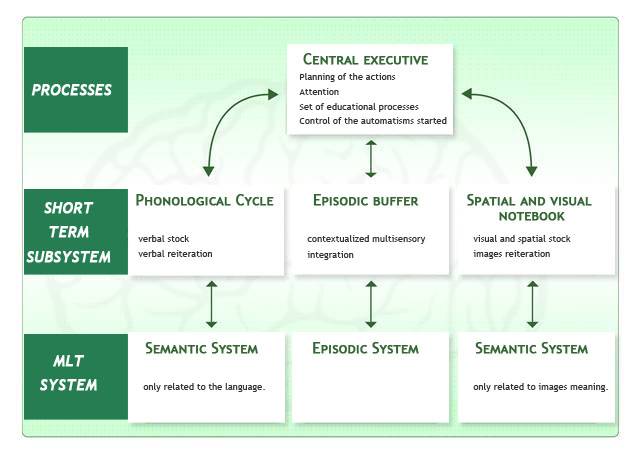

We could identify in the figure below a good summary of the processes considered by the cognitive approach and their relationship with short-term and long-term memory.

1.2.4 Constructivism: situated learning

CConsidering the cognitive paradigm, the question arises whether it is possible to organize knowledge in an appropriate manner for all learners. Furthermore, knowledge about mediated knowledge has caused other criticisms of cognitivism.

To know mediated means the knowledge learned in "class", but not applicable "outside". This type of knowledge is widespread. The twelve-year-old learner has learned theoretically during the geometry lesson how to calculate the width of the roof of his birdhouse. But, in the lab, "it will try as long as it works". The problem occurs in all degrees of study and is also known in high schools and in advanced courses.

For the constructivist paradigm the processing of knowledge is considered a subjective constructive process. In this way it is linked to the context, i.e. the situation, in which it is acquired. By relating it to contextual knowledge, declarative and procedural knowledge is "situated". Learning is therefore an active, self-regulated, constructive, situated and social process (see Gerstenmeier & Mandl 1995). Constructivist teaching and learning models therefore require located learning. The following aspects must be considered in the teaching organization (according to Kerres 2001, p.79):

- the representation of complex, social realities (in place of abstract content)

- the authentic activities of the learners (in place of the activities of the teachers)

- the presentation of multiple perspectives (in place of simple ones) of problems.

Consider 3 approaches that incorporate the following:

- Anchored instruction approach (anchored instruction)

- "Cognitive flexibility" approach (cognitive flexibility)

- "Cognitive apprenticeship" approach (cognitive apprenticeship)

It places at the centre the solution of significant problems in as authentic as possible contexts. In so-called "generative learning environments", learners acquire knowledge and apply them immediately in the exercises.

Highlight multi-perspectivity and multiple contexts. The teaching material must be presented from different perspectives, with different connections, to subsequently allow the transfer of knowledge in obsolete situations.

It transfers the traditional craftsman's apprenticeship as a model to cognitive didactic contents. The apprenticeship of the craftsman is characterized by the fact that the apprentices (novices) first observe the master (expert), and then face and solve increasingly difficult tasks, gradually doing without the assistance of the teacher. This approach takes into account that on the one hand the strategic knowledge of the experts is strongly linked to the situations, on the other the novices understand the "situational" cognitive processes with great difficulty until they have experienced them directly.

1.3 The cognitivist paradigm: learning as a process

Let us take a closer look at the cognitivist paradigm in order to consider the processes of information processing that allow the individual to learn and manage complex cognitive activities such as the use of language, understanding, remembering, reasoning, solve problems, that is, constructive, strategic and metacognitive processes.

Construction processes

The acquisition of a new knowledge is the result of a personal construction of the learners: he uses his previous knowledge structures (his cognitive schemes) to give meaning and rework the new information arriving and to recompose them in a more accurate representation, articulated and complex.

Strategic processes

To face a task or to achieve a goal, learners must develop, choose and adapt flexibly the methods - the strategies - that are particularly effective in that particular situation.

Metacognitive processes

To be able to make an expert and mature use of the knowledge that builds and the strategies that the learners use develops with age and learning experiences a broader metacognitive awareness and a more effective executive control.

Metacognitive awareness is about "knowing how to know", that is the ability to take into account the characteristics of the task, of one's own cognitive processes and activities, of possible solution strategies; executive control refers to the regulatory interventions activated by those who learn to monitor and improve their cognitive activity. The main objectives of these studies and of the educational practices that are inspired by them are aimed at enabling those who learn:

- to rework the different knowledge domains to make them their own tools of thought;

- to learn to learn, that is to take charge of their own learning and to manage it in an autonomous way.

Linked to these three types of processes, there are three very different learning methods for cognitivism:

1.3.1 Learning as a constructive process

The knowledge that an individual builds by hand is kept in memory in organized structures called: schemes, scripts, frames.

Schemes are organized packages of knowledge in which single units of information are brought together and structured together by logical and temporal space relations; they are derived by abstraction through the repeated presentation, in a person's experience, of information or situations that present substantial similarities.

Schemes are composed of some variables (people, events, abstract entities), the relationships between variables, the constraints that specify when a scheme is applicable. For example in the "buy" scheme:

- variables: "seller", "buyer", "merchandise", "money";

- relations: the goods pass from the seller to the buyer, who in return gives him money;

- constraints: the action of "buying" can be carried out only between human beings, the value of the goods and the amount of money needed to buy it are correlated

When a scheme can be successfully applied to new events or new information, it facilitates their interpretation, helps to identify the main constituent elements, makes it possible to make inferences and to complete in a structured way the often fragmented picture of the available information (growth).

When a scheme is only partially suitable for interpreting new events or new information, it can be modified or articulated to make it more effective (tuning);

When, finally, a scheme proves to be inadequate or insufficient to understand new information, a new one can be created, but it must be connected and integrated with the previous schemes, which in turn can be modified (structuring).

A script is a particular type of scheme that refers to recurring situations or activities, in it actions and events are organized mainly according to spatial and temporal relationships. The script performs functions similar to those of the other types of schema.

- propose significant goals for learners

- bring out previous knowledge and put it as a basis for learning

- to stimulate the ability to make thought processes explicit and to build relationships among the knowledge;

- promote self-assessment capacity.

1.3.2 Learning as a strategic process

When a person engages in a task or activity, he must choose, use, adapt or develop strategies, that is, particular methods of managing his cognitive processes in order to achieve the goal he is pursuing most effectively. An inexperienced or novice person to deal with a task has at its disposal a rather reduced range of strategies, it makes use of it little controlled and aware, tends to arrive as soon as possible and sometimes summarily to perform the task. On the other hand, a person skilled in a task has at his disposal many strategies, he chooses the most suitable for the objective, the task, the time available, his cognitive characteristics; if it is necessary to pass flexibly from one strategy to another or adapt it to make it more effective. In other words, its strategic activities are guided, aware, controlled.

This does not exclude that an experienced person, when he / she deals with a very familiar task, puts into practice automatic strategic processes: they are quick, do not require great attentive resources and are learned through the repeated exercise of strategies, which were initially developed in a conscious and careful way.

Strategies are not a stable endowment of the individual, but evolve with age, knowledge of situations and experiences: they can, that is, teach and learn. However, inexperienced people can not be mechanically trained in the use of new strategies, otherwise they run the risk of not understanding their meaning and usefulness and of not knowing how to choose and manage them with awareness and flexibility.

Considering the classroom situation, what can we do to maximize this type of learning?

- orientate the teaching practices and the learning of the learners towards process objectives and not just of product;

- propose the use of strategies when the specific problems are really addressed;

- present strategies as a mode of cognitive functioning and not as content to be learned;

- show the functioning of the strategies and the methods of application;

- to lighten the executive load of the pupil who is still untrained by means of procedural facilities;

- to make the evolution of their strategies known to the learners;

1.3.2 Learning as a metacognitive process

In the cognitive perspective, those who learn should come to take charge of their own learning and to manage it in a flexible and autonomous way, thanks to the progressive development of metacognitive processes, which are implemented on two complementary sides:

- metacognitive awareness (or knowledge)

- executive control

Metacognitive awareness allows you to represent yourself:

- the characteristics of the task to be addressed;

- the strategies that can be used;

- one's mental functioning towards that particular task.

Metacognitive knowledge is often intertwined with personal convictions and beliefs, to constitute personal, informal and implicit "theories" on learning processes; such "theories" are often characterized by a remarkable emotional and emotional tone, are resistant to change, act as a filter against learning processes, and influence their orientation.

The executive control regards the planning, monitoring and regulation interventions activated by those who learn about the cognitive processes necessary to effectively carry out a task or solve a problem.

- prediction makes it possible to estimate in advance the nature of a task, the probable level of performance that can be achieved, the difficulties that can be encountered, the effectiveness of a certain strategy;

- planning makes it possible to organize the best strategies to achieve a certain goal;

- monitoring progressively controls, in each phase, the realization of a plan of cognitive strategies, to continue them, calibrate them better, change them, suspend them or terminate them.

- the evaluation tests a strategy in its entirety and assesses its effectiveness to reuse, modify or abandon it.

Considering the classroom situation, what can we do to maximize this type of learning?

We can identify four main areas of metacognitive cutting instructional intervention:

a) General knowledge on cognitive functioning: the teacher provides, directly or indirectly, information on how cognitive processes are carried out by giving examples during real learning activities and highlighting the factors that facilitate or hinder the achievement of adequate performance.

b) Awareness of their cognitive functioning: the teacher creates the contexts, the activities, the opportunities to help the learner to make contact with their cognitive processes and to analyse their strengths and weaknesses.

c) Wider use of cognitive self-regulation strategies:

The learner is stimulated and guided to:

- propose a clear and meaningful objective, related to the effective carrying out of a cognitive process;

- give instructions and suggestions on how to effectively perform the operations involved in the current process;

- monitor the progress of the implementation of the various stages of the process, wondering if you are going in the right direction, or if you need to adjust the shot, review the objectives or change the strategies adopted;

- take stock of the results obtained, to obtain a greater awareness of the effectiveness - or not - of a certain strategy to achieve an objective under certain conditions.

d) Reinforcement of the positive motivational orientation

The success of the teaching intervention at the metacognitive level depends to a large extent on an intervention also on the motivational level, which ensures an adequate presence in the learner of:

- meaning, importance, value of the objectives it aims to achieve;

- incremental theory of intelligence;

- constructive attributional style;

- sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem;

- positive self-perception of competence.

1.4 Considerations on learning correlates

We feel that we share the vision that learning is modifying through the experience of behaviour, although behaviour is not essential for learning to occur.

The retention of factual information or knowledge, normally classified as semantic memory, which is the core of what most students are encouraged to learn, seems reductive if inserted into the context of adult education and especially if we go to then see the related professionals.

Procedural learning seems to be separable from the ability to learn and remember episodes and events, as the acquisition of new procedural skills may remain intact in severely amnesic patients.

We can, for example, know how to ride a bike without having full knowledge of our knowledge and we can instead know all the rules of chess without knowing how to play chess.

We also believe that the term learning can be legitimately used for each of the 4 areas: remembering a fact, acquiring new information, mastering new skills, developing new habits, and making the difference between the various types of learning is effective.

1.4.1 Attention and learning

Obviously, when new information needs to be acquired, it is necessary first of all to pay attention (for this purpose, the interactivity with the learners that raises the attention curve is particularly important in the design of the courses); secondly, a little practice must be done (this is aimed at exercises and role playing); the material must finally be organized in relation to the pre-existing know-how and then arrive at the final stage of consolidation of the track although this phase is not under the direct control of the subject.

When we say that we must pay attention we believe to say a trivial truth, on the other hand there are situations where the opposite seems true.

Researches on learning during sleep suggest that if information is transmitted to the subject while he is asleep and the next morning questions are asked about what has been presented to him during the night, the subject seems to remember only a small part of the information. However, we do not always sleep deeply throughout the night and some studies, which have monitored the depth of sleep, suggest that learning is achieved mainly during short periods of relative waking stage (Simon and Emmons [1956]).

A similar result is observable even when the attention is distracted by the material to be learned by giving the subjects two simultaneous auditory messages and instructing them to repeat one and ignore the other.

Naturally, attention is not something that is simply present or absent. What happens when the attention is divided between two or more sources of information? One observes what is postulated by Hick's law: the attentive request of a task to be performed increases linearly with the logarithm of the number of alternatives (Hick 1952).

We must consider exceptions to the generalization of the idea that attention is necessary for memory as in the case of subliminal perception and memory under the effect of anaesthesia.

There are data that seem to confirm that patients under light anaesthesia process the auditory information and even if this is not immediately remembered, however, can subsequently influence the subject.

However, the effectiveness of this type of learning remains very low.

All in all, it seems that, despite some problematic cases of remembrance relating to information that has not been given any attention, significant learning can be achieved only by focusing attention.

1.4.2 Motivation and learning

Asking us what could influence the subject's attention, we found ourselves faced with the concept of "motivation" because it probably influences the willingness of the subject to pay attention to the material to be learned, especially when the material to be learned is very burdensome in quantity. of time to devote to learning (Nilsson 1987).

Another situation in which motivation is probably of great importance is in perspective memory, that is, in remembering to do things.

As Mandler's experiments (Mandler, 1967) already showed, even in our opinion the critical factor seems to be how the material to be remembered is elaborated and not why it is elaborated. In this sense the concept of intentionality loses interest, coming to create a glimpse for which even the learner sent to follow a course, which therefore does not individually choose to learn, can make the most of the classroom experience if the contents to be learned presuppose an appropriate elaboration on his part and if this elaboration is encouraged, stimulated and initiated by the teacher.

The intention to learn therefore only helps to the extent that it encourages the subject to pay attention to the material and to process it in the most appropriate way.

How to make the processing take place?

Hasher and Zacks [1979; 1984] have suggested that some features of the environment, such as the spatial location of objects and the frequency with which certain events occur, are automatically stored. An information, that is, is codified without a deliberate effort and is not better considered if the subject makes an effort to remember it than when it is collected incidentally.

Of particular interest therefore for the training designer the full awareness and confidence with those factors that can go to influence the motivation of the learners and with the modalities of the classroom aimed at detecting the motivation and managing the gaps detected.

1.4.3 Practice and learning

According to our ancestors, practice, repetition and frequency are the basis of learning. Although it is not true that learning necessarily requires time and effort, we are aware, after years of providing training to adults, that some types of effort are more profitable than others.

In this sense we fully agree with the concept of distribution of the Ebbinghaus practice [1985]: provided that more exercise means more learning, the relationship between the two is not linear, rather it is better to distribute the learning tests over time, rather than grouping them all together. in one session.

In the planning of the training paths, therefore, two basic principles of learning must be kept in mind:

1. Total time hypothesis, according to which the quantity of material learned is a direct function of the time spent learning

2. A distributed practice is more effective than intensive practice.

Let's try to clarify some points of the hypothesis of total time:

It refers to the time actively spent in learning

The type of processing required from time to time should be kept in mind. Some learning strategies are better than others and therefore the total time hypothesis cannot be expected to be valid even when different amounts of time imply different strategies.

An important exception lies in the effect of distributed practice

The long-term learning process depends on physical changes in the brain. These mutations depend in turn on the neurochemical activity, which can temporarily consume the availability of certain mediators who spontaneously regenerate over time [Kopelman, 1985]. If it is assumed that the learning of a particular task poses particular demands on a specific part of the brain, then it is possible that intensive learning is not optimal because it does not give sufficient time to the underlying chemical state to regenerate. If this type of regeneration takes place over a period of hours rather than seconds, then the crucial factor becomes perhaps the amount of daily practice rather than the length of the rest interval between the different presentations of the material. In this sense, we consider the problem of the length of the rest period between two learning blocks, which must leave the sender with a mental space suitable for the stabilization of brain mutations.

1.4.4 Memory and learning

We have emphasized that repetition alone does not guarantee learning. What is important is what the subject does with the material that he will then be asked to remember. The relationship between type of processing and memory has been much studied in recent years especially with the work of Craik and Lockhart [1972] on processing levels. This work takes up the Atkinson and Shiffrin model that can be summarized as: the longer a stimulus is stationed in the Short-Term Memory (MBT), the greater the probability that it is transferred to the Long-Term Memory (MLT) and therefore the trace last longer.

Craik and Lockhart, with whom we feel to agree fully, added that, rather than focusing on a structural vision of memory, it would have been more appropriate to consider the processes that contribute to remembering. The authors also believed that processing begins at a relatively superficial level and then proceeds towards deeper and richer levels. In terms of training this validates the classroom mode not as a mere filling of an MBT that perhaps will never be consolidated in MLT, but as an aid to the learner to find an effective way to remember, then the suggestion, through experiential moments and presentation of the topics, of a storage mode.

In the literature of the study of memory there are several mnemonics:

- the simple repetition: it does not give satisfaction and if it is superficial, the object is soon forgotten (it does not therefore go from the MBT to the MLT). In addition, if something is repeated mechanically and we are not interested it will be difficult to remember it (it will therefore be in the MLT but we will not be able to retrieve the information). It is the case of an advertisement that the BBC radio did to communicate to the listeners the new frequencies of the radio. The simple repetition of the spot on the radio did not ensure learning. It is not enough how many times a person hears a message, if he does not do it internally, he will go unnoticed. After two months of radio commercials in the message it was so repetitive and boring that it was automatically ignored. In a training context it will therefore be much more valuable to find different ways to underline and reiterate the same contents rather than aiming at simply repeating them.

- repetition and organization for chunks. Miller (1956) had coined the term chunking to indicate that the material to be remembered could be organized into larger units with meaning. He had identified in the "magic number 7 + or - two" the amount of information that could be considered in the MBT. Miller observed that this number was subjective and also depended on the object of memorization, referring to the number of grouped units (chunks). If I have to memorize the phone number 9 3 1 1 1 2 8 9 6, memorizing it repeatedly keeping the units for each digit would make the memorization more complicated than if I grouped the digits into larger chunks: 931 11 28 96.

- by association with things already known: it makes information easier to believe by pairing a new concept with one already known to the learner. The association method consists in creating a stable link between two concepts, so that by remembering one it is possible to remember also the other. In this perspective, learning means to intentionally establish meaningful associations and remembering means to easily retrace the complex and articulated network of associations. Some examples of associations can be the association between the form of the number and concrete objects that resemble each other, the association between the sound of the number and the objects it refers to, the association between the forms of alphabetic letters and concrete objects, the association between numbers and letters of the alphabet, the association between numbers and important dates, the association between the days of the week, the months and the concrete images that characterize them. In a training context you can help learners to make associations by already proposing some solutions and inviting them to create new ones to remember.

- by mediation if the information to be memorized is difficult, between what is easier to understand and information. For example, the cartoon "We are like that" that illustrated the human body's operations made learning information in itself potentially difficult to learn, easy and fun thanks to the mediation of the presentation and the characters who spoke and interpreted various parts and functions in the human body. On this fourth modality the didactic assumptions are based, shifting the role of teacher to mediator and facilitator.

- or organization of information: which can be either suggested by what must be remembered or organized subjectively. See the method of loci for which the organization of known spaces, as if it were our home, we assign information to each room and create a mind map with an organization. When designing a course, you basically work on making sense of the exposure of the contents, making sure to make them easier to learn through proper organization.

- for images: the use of images is very powerful to remember and create links between new and already learned information, or between 2 or more new information to remember. Colourful, moving, static, bizarre images help you memorize better. Richardson, 1980: it is proven that everyone can use mental images. The ability to use mental images varies from individual to individual but the potential is universal. It is easy to understand the correlation between this mnemonic and the use of visual supports to fix the fundamental concepts.

1.4.5 Intentionality and learning

The studies carried out by Norman and collaborators show us how cognitivist psychology studies the perceptual processes and the memory processes in their continuous interaction in which the decisions of the subject have however a fundamental role.

When we talk about interaction between the processes, we want to express a concept according to which the stages identified (acquisition, storage, recovery) do not occur over time in a constant way but rather are particular moments of a continuous flow of information that is interrupted by decision of the subject after, for example, several recovery attempts have been made.

The phenomena of selective and pertinent attention demonstrate that the acquisition process is not a pure and simple phenomenon of mechanical recording of the stimulus, but the last act of a complex concatenation of stimulus analysis processes. For this reason, the commitment of the training is to create the conditions for which there is not a passive fruition of the learner but that it is himself, with strongly maieutic methodologies, to arrive at the cardinal contents of the training paths, so that this elaboration of the stimulus make its memorization more effective.

Sometimes we say that we have forgotten when perhaps we have never received something or we have never paid enough conscious attention.

1.4.6 Emotion and learning

"Emotions", says John Anderson,"exert a great deal of effects on our cognitive apparatus, and one of their roles is to establish the goals we want to achieve."

An emotion, therefore, predisposes to a subsequent action; this is the determining element that must be kept in mind in the formative activity. Faced with a problem, a goal, a path that a learner sets, we can have two types of results. An immediate cognitive block can develop with respect to that project, with the consequent formation of negative emotions (frustration, anxiety, insecurity, etc.). In the best of cases, this leads to a shift in the project (I can not do this and then restructure, modify it, resize it, the project is no longer that but something inferior or different). In the worst case, it is the withdrawal, the escape from the situation that creates anxiety. In both cases, significant changes in one's self-esteem or attempts to assert one's role in an aggressive or completely rejecting manner may occur.

On the other hand, if you are able to glimpse the first steps of the path you want to take, the first partial successes in that direction, you have a confirmation of personal skills, develop positive emotions, satisfaction, joy, satisfaction, security and this predisposes to the next stage, reinforcing the possibility of proceeding further.

It is also shown that emotions significantly affect the learner's memory capacity: the recall of an information appears much simpler if the emotion I am feeling at the time of recovery is the same as I felt at the time of storage.

Many people remember what they were doing on 11 September 2001, while few remember what was for dinner two nights before. Why is it easier to remember an episode that coincides with a strong emotional moment than one that is usually done?

The answer comes from neuroscience. Recently, a group of American researchers at the University of Wisconsin, using techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, have shown that the only expectation to go through a negative or unpleasant experience activates two important brain areas that promote memory. Our brain continually anticipates the course of events, with the aim of guaranteeing continuity between past, present and future; obviously all this flow of thoughts is based on one's own memory and strained - in unconsciousness - in the dream world.

The researchers have identified two regions of our brain that are very active during an emotional event and in the thought of it: amygdala and hippocampus (the amygdala has long been associated with the consolidation of emotional memory and the hippocampus is essential in episodic memory to short term).

Since the hippocampus deals with the function of selecting the information to be transferred to the secondary memory, it follows that learning and forgetting are greatly influenced by positive and negative emotions. If you feel disgust with a subject, the possibility of learning it is scarce. A positive basic learning (playful learning) stimulates the rate of transfer to secondary memory, whereas a negative attitude makes learning more difficult. A positive attitude can arise spontaneously, but it can be greatly increased by stimulating motivation, even self-motivation.

Theories of learning and training

Berelson and Steiner define learning as "changes in behaviour deriving from previous behaviours in similar situations", in this perspective training would have the task of influencing subsequent changes and also, consequently, subsequent learning. In this sense, for the trainer, learning brings with it the following aspects for learners:

- knowing intellectually or conceptually something that was not known before;

- be able to do something that you were not able to do before;

- ccombine two elements learned in a new understanding;

- be able to apply a new combination;

- be able to understand and apply what is known.

We tend to think that a trainer really interested in learning must, rather than devote himself to a theory only as the only paradigmatic reference, be able to continuously monitor the implicit and explicit feedbacks of learners, always keeping their level of learning under control. This will bring a watchful observer to acquire an expertise that can be spent from the design phase of training interventions to their delivery, with a view to continuous improvement.

2. ANDRAGOGY

The considerations made up to here apply to any type of learning, but we know that company training is to affect the knowledge of adults, who also have in the process of forming their specificities.

Andragogy is a unitary theory of adult learning and education. The term was coined as opposed to that of pedagogy which derives from the Greek παῖς pais, child, and ἄγω ago, lead. It is a model focused on understanding the diversity of learning needs and interests of adults compared to children, which has found its greatest exponent in Malcom Knowles.

Adult education was probably the very first form of systematic education. All the great masters of ancient times taught adults and not children. Thanks to their experiences with adults, these teachers considered learning a process of active research, not as a passive reception of content, and then invented techniques to actively involve learners.

On the contrary, the first schools that appeared in Europe in the seventh century had as their main goal the indoctrination of the dogmas of the faith of monks and priests, for which they elaborated different methodologies. The pedagogy that derives from it gives the teacher the full responsibility of the decisions regarding the contents, the modalities and the evaluation of all that will be learned. This is an instruction led by the teacher, which leaves the learner only the subordinate role of following the teacher's instructions.

The term andragogy was officially coined in Germany in 1833, by Alexander Kapp, and then reconsidered in Germany, Holland, Great Britain and the United States only more than a century later.

Numerous researches (Bruner, 1961; Erikson, 1964; Getzel and Jackson, 1962; Bower and Hollister, 1967; Cross, 1981; Iscoe and Stevenson, 1960; Robinson, 1988; Smith, 1982; Stevenson-Long, 1979; White, 1959; ) suggest that, as individuals mature, their need and their ability to be autonomous, to use their learning experience, to recognize their willingness to learn and to organize their learning around real life problems they grow constantly from infancy to preadolescence and then very quickly during adolescence. In relation to a high degree of independence, pedagogy is applied inappropriately.

2.1 Knowles theory

The andragogical theory developed by Knowles is based on the following fundamental assumptions:

1. The need to know: adults feel the need to know why it is necessary to learn something. Tough (1979) found that when adults begin to learn something on their own, they invest considerable energy in examining the benefits they will gain from learning. The first task of the learning facilitator is to help the learners in this awakening of awareness.

2. The concept of the learner's self: as a person matures and becomes an adult, the concept of self-moves from a sense of total dependence to a sense of increasing independence and autonomy. The adult must feel that his concept of self is respected by the educator and therefore must be placed in a situation of autonomy (as opposed to a situation of dependence).

3. The role of experience:the greater experience of adults ensures greater wealth and the possibility of using internal resources. Any group of adults will be more heterogeneous - in terms of background, style of learning, motivation, needs, interests and goals - than what happens in groups of young people. Hence the great emphasis placed on adult education on the individualisation of teaching and learning strategies, experiential rather than transmission techniques and peer-help activities. Greater experience may also have negative traits in the sense of greater rigidity in mental attitudes, prevention, presuppositions and closure with respect to new ideas and different approaches. Another reason that emphasizes the importance of experience is that while for children, experience is something that happens to them, for adults it represents who they are. That is, they tend to derive their personal identity from their experiences.

4. The willingness to learn: what is taught must improve skills and must be able to be applied effectively to everyday life.

5. Orientation towards learning: it must not be centred on subjects but on real life. In fact, adults learn new knowledge, understanding, skills and attitudes much more effectively when presented in this context. This point is of crucial importance in the teacher's presentation methods, in the definition of objectives and contents and in the more general planning of the training intervention.

6. Motivation: in the case of adults, internal motivations are generally stronger than external pressures. Tough (1979) found that all adults are motivated to continue to grow and evolve, but that this motivation is often inhibited by barriers such as a negative self-concept as a student, the inaccessibility of opportunities or resources, the lack of time and programs that violate the principles of adult learning. In this, the promotion of self-determination also plays a fundamental role, satisfying the innate psychological needs of competence, autonomy and relationship. Competence consists in feeling able to act on the environment by experiencing feelings of personal control. Autonomy refers to the possibility of personally deciding what to do and how. The need for a relationship concerns the need to maintain and establish links in the social sphere.

The andragogical model, according to Knowles' conception, is not an ideology but a system of different alternative hypotheses.

After the 1970 publication to the author, the experiences of numerous elementary and middle school teachers were communicated, applying in some contexts the successful model and adult trainers who instead claimed that this model did not work. This means that the trainers are responsible for verifying which hypotheses are realistic in a given situation. For example, when learners are very dependent (such as when they enter a totally extraneous content area), when they have never actually had experience with a certain area of content, when they do not understand their relevance to the tasks or problems of their real life, when they need to accumulate a certain set of basic content for a given performance and when they do not feel the need to learn that content, then they must be taught by applying the pedagogical model.

2.2 Adult education modelsi

We try to elaborate very quickly a taxonomy of adult education models, in the belief that educational practice has to deal with the broad and complex framework of possible pedagogical choices.

2.2.1 Pedagogical model

Training as an increase in knowledge and skills in view of the exercise of a profession or a role. Centred on school education. He refers to Bloom's Taxonomy and to the model of Gagné's hierarchical learning. It can be set according to a linear approach (school model tradition), or on a modular approach (Bloom's school curriculum theory).

2.2.2 Andragogical model

Training aimed at adults as a person who has to change herself in relation to the objectives and the roles to which she is called. It is centred on the validity of the processes rather than on the contents. Knowledge is first of all restructuring of knowledge and behaviour. It can be set according to 4 approaches:

- psychosocial approach: when the goal is the improvement of the individual through the improvement of communication skills between the individual and the group

- clinical approach: it arises from the application of psychoanalytic models to the group rather than to the individual

- organizational development approach: the trainer works directly in the workplace, works on the diagnosis of the problems of the company and on individual support for the management, intervening on the groups, on the relationships between groups and on the tasks.

- organizational learning approach: based on the reading of the environment, that is the cultural and organizational contexts of the company. It moves from Bateson's eco-psychological theories.

2.2.3 Technological model

Focused on the use of new technologies intended as a formative environment of high impact for the student but also ability to create new learning spaces (from hyper textuality, to recording, video production, programming, etc.). The central role is assigned to the medium itself, meaning multimedia as a multimedia classroom or as a synergy of "medial atoms" able to create educational “micromonds”. It emphasizes the importance of considering technologies in relation to their functionality in achieving a specific training objective. Without prejudice therefore, that they must be used only if they represent the best solution, the multimedia technologies allow the integrated use of different channels, they favour the bidirectional communication and allow the discussion of topics that with traditional technologies could not be addressed.nicazione bidirezionale e permettono la trattazione di argomenti che con tecnologie tradizionali non potrebbero essere affrontati.

2.2.4 Socio-educational model

Centred on the idea of training as a contribution to the social and development of the ability of the individual to intervene on it. It completes the training to strengthen the heuristic capacity of the subject in his social commitment, the creation of awareness and maturity in the individual to become a promoter and actor of social and organizational change.

2.3 Experiential learning

Speaking of Andragogy, Kolb's experiential learning model seems to us particularly useful in the field of company training. According to this model, learning would be a 4-stage circular process:

1. concrete experience of a given reality that initiates and concludes the learning process;

2. observations and reflections, related to the experience, which are carried out by analysing the same from different perspectives according to their perceptual field (operational and conceptual reference frameworks);

3. formulation of abstract concepts capable of integrating previous observations and reflections into pre-existing theories and giving them a meaning of general validity;

4. empirical verification of the theories formulated through the experimentation of the extensibility of such theories in new decision-making situations.

Each stage of the model corresponds to a different learning attitude, so:

a. concreteness

b. reflection

c. abstraction

d. action

Each individual, when he completes the whole learning process, passes through these 4 stages with his rhythms and specific individual modalities.

Starting from these assumptions and reflections of Kolb, we take into account the learning style according to the following taxonomy:

- "converger": characterized by high scores of action and abstraction, led to the practical application of concepts;

- "diverger": characterized by high scores of concreteness and reflection, brought to the creative and emotional imagination and interested in human rather than technical problems;

- "assimilator": characterized by high scores of abstraction and reflection, led to the creation of theoretical models through observation and induction, but scarcely interested in their application;

-"accomodator": characterized by high scores of concreteness and action, led to the realization and adaptation with respect to the surrounding reality.

The purpose of this taxonomy is to maximize the effectiveness of training by adapting the transmission of content to the learning style of learners.

2.4 The hierarchy of learning by Gagnè

The basis of this classification is the need to relate the choice of objectives to a concrete hypothesis of the different types of learning. The typology is not qualitative but instrumental in nature. The levels in hierarchical order are:

1. signal learning. It reacts in an emotional and automatic way to certain signals. Condition: close presence of the two stimuli, the one that gives the signal and the one that produces the effect;

2. learning of stimulus-response connections. Condition: the exercise must be gradual and must be connected to a positive reinforcement action (the presence of a guide);

3. concatenations. Sequences of multiple stimulus-response connections are learned. Condition: each link in the chain must have been acquired and presented in contiguity with the following exercise;

4. verbal association. Condition: an association is created between the first verbal element and the second one, inserting a codifier that acts as a mediation;

5. learning of discrimination: one learns to give different answers to apparently homogeneous stimuli. Condition: presence of specific chains that allow the recognition of stimuli

6. alearning concepts: opposite of the previous one, leads to a common response to different stimuli. Condition: a wide variety of experiences and exercise;

7. alearning of rules: chains of concepts are created giving rise to principles. Condition: possession of concepts, exercise;

8. problem solving: we get to combine a series of rules and solve new problems. Condition: you possess the essential principles and train you to their combinations.

2.5 Elaboration of an andragogical model

Meeting the client and trying to understand the logic and requests, we came across, in companies, in different ways to pass content, including:

a. Information: indicates any communication of a given fact to another person. It is an activity that proposes the increase or improvement of knowledge with respect to a given topic. The "formative" action of an information depends on the fact and on the extent to which the informed assimilates the information itself. Being an assumption of knowledge, it affects almost exclusively cognitive processes. Research in learning psychology and experimental psych pedagogy suggest what are the least effective ways to use information:

- a strong emotional tension and anxiety that make the subject more inclined to functional fixity;

- functional fixity, i.e. the phenomenon that consists in considering an object in its conventional meaning, when it must be examined in a different context, the need to adapt the information to the criterion that the learner adopts to solve a given problem;

- the need to adapt the information to the criterion that the learner adopts to solve a given problem;

- negative information, i.e. information about what something is not, which proves to be particularly useless to those who try to grasp a concept.

b. education: refers to a transmission of concepts, supported by an educational purpose. It represents a planned process and is the result of the interaction of several moments: the person who instructs, the topic of education, the student. The American psychologist Bruner (1967) has developed a "theory of education", a prescriptive theory in that it formulates rules concerning the most effective way to achieve a certain knowledge or normative ability by providing criteria and establishing the conditions to satisfy it. Bruner argues that education is a temporary situation, since its purpose is to make the student self-sufficient and the teacher has the task of correcting the learner in a form that allows the latter, at the end of the teaching process, to assume personally this corrective function.

The theory developed by Bruner aims to improve the learning process (rather than to describe it) through four main objectives:

1. to establish which experiences are most likely to generate a predisposition for learning in the individual

2. specify the way in which a set of cognitions must be structured to be readily understood by the learner (the effectiveness of a structure depends on its ability to simplify information, generate new propositions and make a set of cognitions more manageable)

3. specify the optimal progression with which the material to be learned is presented

4. specify the nature and rhythm of the rewards and punishments in the teaching and learning process

The predisposition to learn, Bruner points out, is linked to the regulation of research behaviour: activation, maintenance and direction. The exploration of possible alternatives, in essence, requires a stimulus that sets it in motion, an interest that food is a criterion that prevents it from proceeding blindly. Since every attitude is conceptualized for an important part in terms of "internalized activity", Bruner shares the Piagetian assumption that "the activities that are performed in the physical environment end up becoming internalized and becoming mental operations"

c. training: refers to the acquisition of manual or intellectual skills (skills). It implies a formative and systematic function intended to modify, over time, according to a predetermined program, the behaviour of people at work, the "know-how". All the training processes base their bases on the psychological mechanisms of learning. In adult education, training is a particular educational activity aimed at satisfying the need to learn the correct practical use of equipment and devices or procedures. The training activities must take place in contexts that are progressively similar to those that characterize the real work performance required. It must be combined with the availability of information and instructions and with the task of verifying comprehension.

d.training:it is an educational activity aimed at adults to acquire basic skills or general knowledge, it is one of the most profitably used means to facilitate the learning processes of adults. Training tends to the overall development of potential and to the increase of psychic abilities, with particular regard to the emotional sphere and to the change of attitudes. It acts on the sensitivity, on attitudes, on the potential of workers and is identified with psychosocial intervention. According to a classic definition of the French social psychologist Goguelin (1973) "information is a 'knowledge' (cognitive area); training a 'know how' (operational area) and training a 'know how' (behavioural area) ". The worker training program must be inserted organically into a business strategy that also includes the identification of any organizational-relational obstacles to change. Having an appropriately informed, trained, educated, trained and equipped staff is a business opportunity. In relation to what has been analysed, we consider the following to be fundamental elements of the creation of an andragogical model:

In relation to what has been analysed, we consider the following to be fundamental elements of the creation of an andragogical model:

1. Ensure a climate conducive to learning. Both from the point of view of the structures (functional, welcoming, ...), both from the point of view of resources (rich, usable, ...), both from the point of view of the organization (functional, non-hierarchical, communicative, ...).

One might think that the lecture given to adults may be easier to design as it is given to subjects less in need of being stimulated to attention and participation as more mature but is not entirely accurate. Even the adult learner needs special measures and the more the change you want to work in the learner touches the values and the beliefs rooted the more the context factor of the training takes on greater importance. For this reason, in the traditional classroom we tend to combine methods such as outdoor that facilitate the questioning of one's own point of view.

2. Create a common design mechanism. Each training intervention is based on structured rules and good practices so that the individual designer or individual trainer can base their choices and their behaviour on a shared and appropriate know-how without having to risk an improvisation that already sees in its irreplaceability a safe little congruence with an activity, such as training, which sees replicability as a key requirement.

3. Diagnose learning needs. Elaborating a model of skills. Evaluating the discrepancies between the skills model and the current level of development of learners and then formulating learning objectives.

4. Design a model of learning experiences.Not the simple "program" but a real learning project, based on a series of interrelated episodes.

5. Implement the program (manage learning activities). The management of the classroom is the least obvious in the training landscape, different classroom styles completely change the effectiveness of the course and its usability. For this reason, it is essential to align the trainers by adapting each time the style to be kept in the classroom to the course and to specific learners.

6. 6. Evaluate the program.All the didactic paths must be validated to allow the evaluation of the didactic program and its implications, of limiting the classroom style and the organization of the contents, as well as of verifying the times and the modalities of the exercises.

3 REMOTE ANDRAGOGY

Increasingly, in order to save on teaching time, e-learning is increasingly used to complete or even replace lectures. We ask ourselves first of all what the effectiveness of this modality can be and how it differs from andragogy in the presence.

Let's start again from theories on memory. We have said that working memory is active memory, in which ideas are generated and learning takes place. This type of memory has a very limited capacity. When the working memory is occupied with even the smallest amount of information, its processing capacity decreases rapidly.

On the other hand, long-term memory has a wide capacity for information and serves as an archive of knowledge and memories. It is for this reason that e-learning is an effective teaching tool: precisely because it allows to learn the essential concepts, without weighing down the working memory and at the same time promotes the storage of information in the long-term memory.

In support of these convictions, according to a recent discovery by Sander Daselaar of the University of Amsterdam and Roberto Cabeza of Duke University published on PLoS Biology on January 14, 2009, it has been shown that to remember or learn there is an exchange lever that alternates two separate tracks, one that allows one to learn and the other that allows one to remember.

As part of the study, the researchers monitored the brains of a group of young people with functional magnetic resonance imaging while the volunteers were struggling with a game, in which they had to learn words and simultaneously recall images. It emerged first of all that the two activities carried out together tilted the brain that does not show itself capable of completing them at the same time. We have also seen that when we switch from learning mode to that memory, or vice versa, we activate a region of the left front of the brain, an exchange lever that allows it to quickly switch from memory to learning and vice versa.

In other words, the memory of information seems to inhibit the learning of new information that is present at the same time as the subject's attention. At magnetic resonance this cognitive outcome has translated, in case of success in the memory of words, in a less activation of the time areas involved in learning.

From this study it follows that the most effective method for the comprehension and memorization of the lessons will be to clearly distinguish the two phases: at first it will be necessary to concentrate on the understanding of the concepts, eventually supported also by the visual memory of an image. secondly, we will concentrate on remembering and memorizing the already assimilated concepts.

According to us, e-learning will therefore be effective as it will allow us to review the contents several times in different ways to strengthen both working memory and long-term memory. In the aforementioned investigation by Matthew P. Murgio, particular functional modalities of our memory had already been discovered. Greater results are obtained by speaking, writing and applying what has been learned.

It follows that individual mnemonic skills are best used with e-learning if the lessons can be reviewed several times (50%), if there are modes of self-assessment and sharing that stimulate interaction (70%), if they are planned exercises allowing to apply the acquired concepts (90%).

Going to resume the various learning paradigms analysed in the opening of this work, for remote andragogy we believe that the constructivist paradigm offers us the greatest ideas in its placing the learning subject at the centre of the learning process (learning centred). As an alternative to an educational approach based on the centrality of the teacher (teaching centred) as the undisputed depositary of universal knowledge, this current of thought assumes that knowledge:

- it is the product of an active construction by the subject;

- it is closely linked to the concrete situation in which learning takes place;

- born from social collaboration and interpersonal communication.

Therefore, there is no "right" knowledge and "wrong" knowledge, as there are no optimal styles and rhythms of learning. Our greatest effort remains to remain within the paradigm of Bruner (1992) according to which knowledge is a "making meaning", that is to say it is a creative interpretation operation that the same subject activates every time that wants to understand the reality that surrounds it.

Accepting and promoting the inevitable comparison deriving from multiple individual perspectives is one of the fundamental aims of those who plan training so much that learning should no longer be seen only as a personal activity, but as the result of a collective dimension of interpretation of reality. The new knowledge is built not only on what has been acquired in past experiences but also and above all through the sharing and negotiation of meanings expressed by a "community of interpreters".

The learning becomes therefore significant (Jonassen, 1994), the ultimate goal is not the total acquisition of specific contents pre-structured and given once and for all, but the internalization of a learning methodology that progressively makes the autonomous subject in their own cognitive processes.

Constructivism has not developed an univocal didactic model, absolutely valid, but rather limits itself to indicating a series of presuppositions that must be respected in order to make the training activity really respond to the contingent needs.

In order to produce knowledge at a distance, it is therefore necessary to create a "learning environment", which, as Jonassen argues, is much more difficult than designing a series of traditional teaching interventions.

"This is because there are no predefined models for constructivist learning environments, and for many they will never even exist, as knowledge building processes are always placed in specific contexts, so the types of learning support programmed in a given context in all likelihood will never be transferred to another "(Jonassen, 1994).

We agree with the set of fundamental recommendations that such a learning environment should, according to Jonassen, always promote:

- emphasize the construction of knowledge and not its reproduction

- avoid excessive simplifications in representing the complexity of real situations

- present authentic tasks (contextualize rather than abstract)

- offer case-based, real-world learning environments rather than predetermined instructional sequences

- offer multiple representations of reality

- encourage reflection and reasoning

- allow constructions of knowledge depending on context and content

- favour the cooperative construction of knowledge, through collaboration with others

The learner must be enabled to activate an active exploration that is in keeping with his own interests and / or motivations for learning new knowledge.

All this does not mean that a self-learning process is promoted, but that it is the same structure of the offered materials and of the promoted teaching activities, which trigger a cognitive process relevant to the same subject: the learning experience is based on a process flexible re-adaptation of pre-existing knowledge according to the needs posed by the new training situation.

Case studies, problem-solving and simulations are, for example, excellent teaching strategies. Even when training is aimed at the memorization of concepts or definitions, their application in a practical activity can make them internalize in an extremely simple way.

Presenting more significant factors in a "problematic" situation also develops in the student an investigation activity which is functional to the production of effective decisions.

Re-elaborating the knowledge possessed according to new needs promotes creative thinking.

In a group of work and / or cooperative learning the fact of being able to exchange new ideas and opinions, through the sharing of diversified skills, increases the ability to find optimal solutions in the shortest possible time

If we were to find a formula to combat the challenge to increasing competitiveness, we would think to equip the subject with a cognitive methodology that progressively develops metacognitive skills and critical thinking.

In the training field the emphasis on cooperative learning and the communities of learning find ample space and new opportunities in new educational technologies.

The telematics therefore becomes synonymous with a tool that allows access to countless resources, as well as "amplifier" as it is a collaborative tool: the contents are no longer received by a single source but are articulated and "built" through forms of interpersonal communication functional to the activation of a critical, reflective and shared thought.

Today, technologies offer the possibility of respecting and emphasizing the individuality of the subject who learns in an independent but at the same time engaging space-time within a stimulating learning community.